This post discusses suicide.

On February 3rd we lost Swostika Adhikari, a host family cousin, to suicide. She was 16 years old.

***

"How is your pen pal program going?"

A high school student sat on a stool and looked at me with curiosity from her porch. The book she had been studying balanced placidly on her knees. I had come to her house to update her grandfather about a beekeeping project he was interested in.

It had been some time since I visited her school to announce a pen pal exchange I was setting up with a friend of mine in the United States. I explained that we had made our selection of Nepali pen pal participants and that I had been planning to get the students together for a meeting when Swostika died.

"It wasn't a good time," I said. "So I'll probably come back to school in a week or so." I wondered what the mood was like at school now. What the students were going through. What they were thinking. Were they talking about it?

I hesitated.

"How are the students feeling?" I asked.

The girl's face fell. I watched her struggle to find the right words.

"Too much sad," she said, finally, in English.

I nodded. We were quiet. Sitting together with the weight. I wanted to offer something more to support her -- something, anything. But then a passing neighbor interrupted us and swept the moment away.

***

Today is the 8th day of Swostika's mourning rites. I write this after having returned from her family's house where dozens of family and community members have been gathering each night in memoriam.

I think of her often; I think of her now. I write this and think of the time she and I squatted by the fire as she cooked dinner -- I remember asking her about school, about her future. What class are you in? What do you learn at school? I asked. Do you want to go abroad to study or do you want to stay in Nepal? I think of when I visited her class two weeks ago to announce the pen pal program: I think of her face in the sea of students, and the stark and aberrant stoicism on it that struck me at the time. I think of her leaning over me to hand her mother a pack of dried coconut and fruit pieces. That was the night before she was found. I think of her long, black hair draped over the wooden pyre as her body was set ablaze on the riverbank. I think of her suffering, alone. I think of her dying.

I think.

I hope.

A year before I left for Nepal I experienced my first loss from suicide. My friend Julian killed himself in his apartment a few hours away from where I lived. Many of us knew that he had wrestled with depression for some years, but none of us ever imagined that he would be killing himself; if we had, his story might have been different. Perhaps, like him, Swostika had been struggling with depression. Perhaps.

***

"What is this?" sighed a family member one night, throwing up their hands.

"Why are they doing this to us?

In our time, no one did things like this -- our mothers and fathers never did things like this. You grew up, got married, and lived your life in your village even if it was hard. No one killed themselves.

Kids these days on their mobile phones watching TikTok videos and getting ideas about such things. Sitting on their phones all day, watching, watching, listening to someone say this, say that.

It's all crap."

***

I am coming to understand that, as a colleague Jim Damico stated, "Suicide is more prevalent in Nepal than anyone really admits." It is a serious problem here. One I had been alerted to after arriving 8 months ago. In that time I have come across the cases of:

- The student in a nearby village who killed themselves after failing an important exam. ("It's why she always calls me during exam times," explained Manisa, my host sister. She was talking about aamaa. "She's afraid that it will happen to me.")

- The wife of a villager with a speculated troubled family life who killed herself in their city house.

- The mother of a friend of a friend who recently killed herself.

- Someone I met who revealed to me that they were suicidal and had attempted suicide in the past.

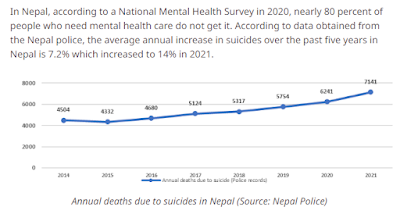

In fact, it is such a problem that suicide rates are up 72% compared to 10 years ago -- with little sign of slowing. Every year since 2017 suicide cases have increased steadily by about 7% per year. And 6.5% of adults who live here currently experience suicidal ideation. So state official Nepali police reports and a national health survey that was released in 2020.

I am not in a position to remark on the prevalence of suicide in Nepal compared to America. What I do know is that it is a problem in both of our countries and for countries around the world. And while the paths to suicide may be vast and myriad, the darkest depths of human suffering can be found in every case. And bits of that suffering burn slowly into the hearts of those left behind.

***

About a week after Swostika died I was at the high school math teacher's house.

"How are the students at school?" I asked him.

He considered this for a moment.

"Tikkai chha," he said. They're OK.

"After bahini died..." Here I paused, watching him cross his arms as I spoke, "... there hasn't been any talk about it at school? Or has there?"

I tried to imagine a high school in the US. I imagined teachers discussing the issue with their students, offering their support. Encouraging them to talk about it together with their school counselors and other trusted adults. I imagined an assembly. An evening vigil.

"No," he said.

Time stretched into a pregnant silence.

"People don't talk about this kind of thing in Nepal, huh?" I said.

"What is there to say?" he replied grimly.

***

What is there to say?

There is a lot that I could say: about the stigma of mental illness, the lack of its discussion. The poverty, the debt. The troubles. The endless combinations of circumstances and misfortune that lead people to feel trapped with no way out. The ubiquity of it. The need for support. And the support we can give.

Ultimately, people are not getting the help they need. Resources are scant, though there are organizations doing good work here in Nepal. It is not enough. And many people here do not talk about mental health, mental illness. They don't know that they should. And don't know how to.

I hope that I can put together a mental health program for the school in the future. I hope the community, and the students, are supportive of the venture when I propose the idea. But we are still in the throes of grief, and now is not the time; so I leave that for another day.

***

I messaged one of the English teachers three days after Swostika's death.

"How are the students doing at school this week?" I wrote to him in English. "I'm sure you know about bahini's passing." The grief-stricken emoji I added hung its head sadly at the end of my sentence.

He wrote back with a namaste emoji in polite greeting. "All are well."

***

By coincidence I was finishing a reading and notation of a practical guide on the counsel of suicidal people when Swostika killed herself. "Counseling Suicidal People: A Therapy of Hope," it read on the cover. The first half of the book counseled on how to have frank conversations with suicidal people, maintain nourishing relationships with them, and keep them as safe as possible; the second half was about supporting patients from the perspective of a mental health provider, including an index of strategies to explore with them.

While going through this book I was particularly struck by one passage that dictated that, as a therapist, you must commit, consciously and wholeheartedly, to the life of every patient without fail. For in the therapist-patient bond, the moment you as the therapist begin to doubt, or find yourself wavering, you have failed them. From the start you must decide that everybody lives and nobody dies.

I hope that one day we live in a world where that is true.

Good reflection on the situation

ReplyDelete