Throughout my service I've had moments finding myself imagining my daily life here through the lens of a video game.

As I think about this, I realize: it's totally a video game. Especially the experience of an agriculture volunteer.

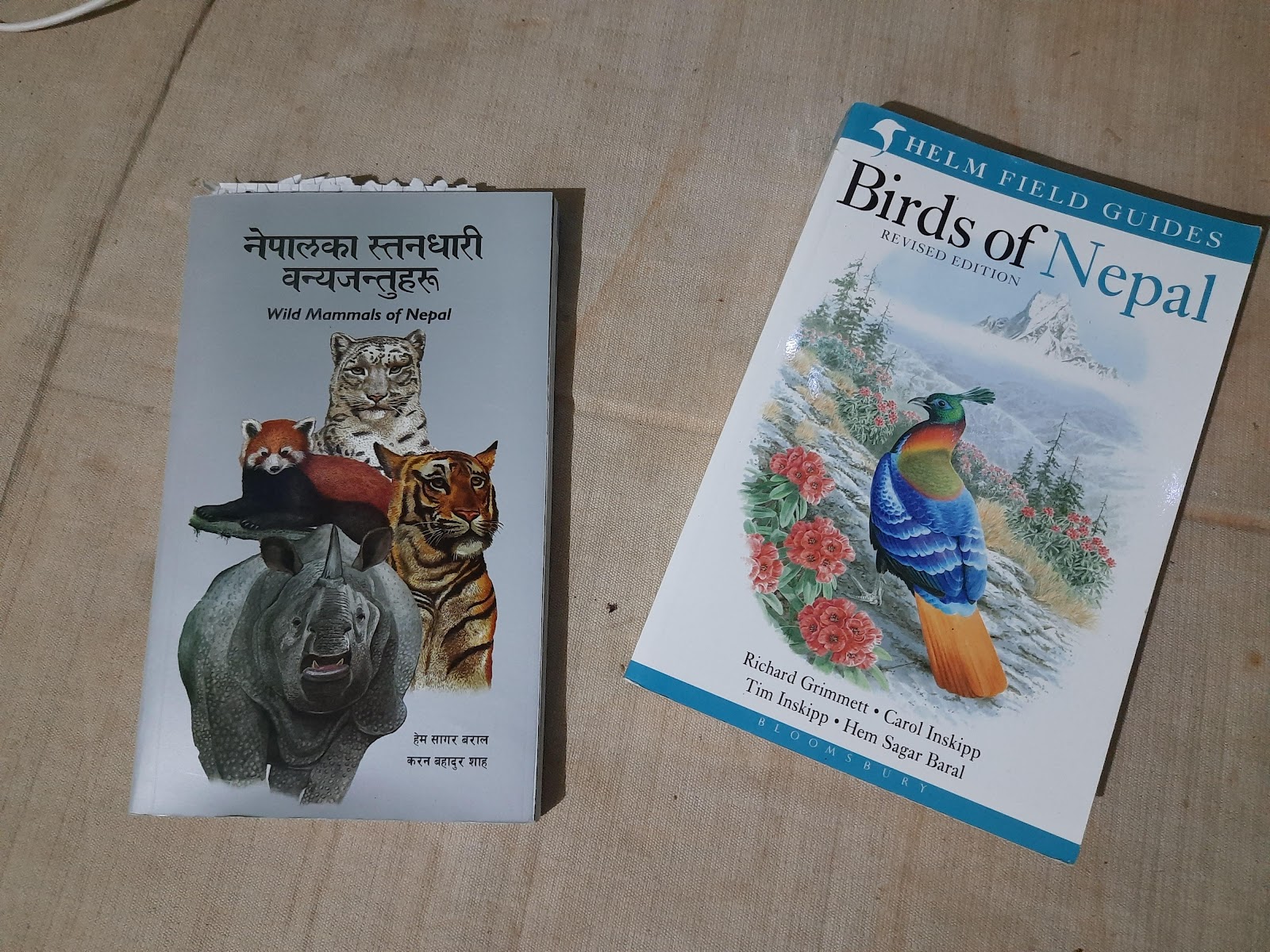

Like, you're just a little guy wandering my village, bumping into NPCs, clicking through their repetitive dialogues, and completing periodic fetch quests for them, meanwhile discovering new areas of the map. There's bartering in lieu of monetary transactions; when you wander into the jungle and grassy zones there's a random chance that you will get attacked by leeches and afflicted by the subsequent Leech debuff; and sometimes it pays to go out of your way to explore because the NPCs you meet end up giving you mood buffs and leave you with tasty snacks in your inventory. You have your main objectives tracking in your quest log but you end up getting distracted with some other random activities and unexpected wanderings. Or, when you set off on a whim to pursue a side quest that has you hunting up some special berries for a jam recipe, there are three possible areas where they could be found that are only vaguely described by villagers, and you have to stumble around and discover all three potential spots before the berry bush finally spawns. And while you are doing all of this, you try to complete entries in your bestiary guidebook which means searching for different species of animals, insects and plants in different areas, times of day, and seasons. (It would be nice to achieve 100% completion for the bestiary - but you're not hellbent on it - so you're going to casually play, occasionally go out of your way to look for new entries, but not try too hard, and see how far you get).

You know - normal video game stuff.

"Sometimes I feel like an NPC sitting in front of the house on a stool [with] player characters coming up to interact turn by turn"

I said this at the beginning of service when I had just arrived in village and was getting my bearings.

Village life is open. Beyond house fronts being rather open-air, there are always people outdoors doing chores, wandering, moving around, and visiting other villagers -- without appointments or calls or expectations.

It's not uncommon to sit around in slow time. Which means you may be doing nothing at all for extended periods -- literally, nothing. For example, sitting on a stool in front of your house and watching the passersby. I often did this in my first weeks at site and found the number of people who wandered up interesting, passively watching someone who stopped by on a morning walk. Another villager trudged slowly through our patio on their way home from harvesting fodder for their livestock, borne down with a heavy basket of grass on their back. Or an extended family member who dropped off a bag of tomatoes. And others, at that time unnamed, who cycled past the house as a point in their day. Saying hey.

This open nature of connection and community is something I've come to not only appreciate but live and breathe. (Part of why it works and feels good is that it is an open, visible, accessible, and walkable community, which is lacking in the States -- and which I could go on about, but won't here). I know with certainty that this will be a sore point of transitioning back to Western society. You mean I have to schedule quality time with people weeks in advance instead of taking 3 minutes out of my way to walk to their house and drop in? And now schedule even phone calls?

"Sorry, I left my phone in the other room," a friend from the States told me one evening. I had phoned without advance and they had missed my call. "No one really calls me unless it's an interview or something. I heard my phone ringing and thought it was weird."

I am reminded of myself, four years ago, moving into an isolated duplex unit without immediate neighbors in a rural community and introducing myself to the nearest house with homemade baked goods. I felt like I was a callback to the 50s -- simpler times, where all it took was a tasty treat and a knock on the door to begin to forge a neighborly connection, instead of six months of awkwardly trying to ignore each other's presence in the elevator before feeling (un)comfortable enough for a stilted conversation.

Bring back talking to friends on long phone calls! Bring back unannounced house visit culture! Bring back knowing your neighbors - like, at all!?

I feel like a boomer. But, you know, maybe they are on to some things...

"Sorry man it's not personal - you just happen to be the 213th NPC in service and i need to skip this dialogue and get back to this quest aight"

Something else you deal with as a host-country-language-speaking expat is rote small talk.

I remember reading the blog of a Peace Corps Volunteer while I was researching and applying to serve oh-so long ago. The exact details evade me but the author somehow lamented on this unfortunate reality of service - that is, having the same conversations with strangers ad nauseum. At the time I thought: well, that makes sense. It would get tiring, but I can handle it.

And, well, I was right. I can. The amount of patience I started with and the amount I have now to entertain these conversations, however... let's just say they differ.

It doesn't sound so bad. And at first it isn't. But after hundreds of iterations it starts to wear you down.

At this point, the second that an interaction with a Nepali stranger begins, it's as if a probability tree of the conversation appears at the corner of the game interface in low opacity, waiting to be induced with one of the key conversation starters. There's the usual "Oh wow, you can speak Nepali!" and "Where are you from?" and the iconic "Where are you going?" or (equally probable) "Where are you coming from?" to break the ice; then, within the first two minutes, a 90% chance that at least one of the following questions/comments will occur:

> "Are you married?"

> "Take me to the US with you!"

> "How many older sisters/younger sisters/older brothers/younger brothers do you have?"

The wheel of fortune spins in randomly-selected algorithmic fashion and lands on the first possible option. "Are you married?" Someone will begin asking me. I inform them that I am not. Before I even finish saying this my brain has primed itself for the probabilities of their next response:

> "Well, then you should marry a Nepali guy and then live here for the rest of your life! How about it?(70% probability)

> "Why not?" (20% probability)

> "How old are you?" (10% probability)

"Well, you should marry a Nepali guy and then live here for the rest of your life! Don't you think?" they ask me excitedly. Full of pride. The first 20 times I heard this, it was amusing. After 150 times a lot less so. I say no, with a number of expressions that I withdraw depending on my mood and who I am talking to -- I don't have much time left in country and it's not practical, I say to one person; I need a lot of time to get to know someone if I am going to marry, I say to another; in America you don't need marriage for a successful life, and besides, my parents' marriage ended in divorce, I tell a third.

"No," I say.

> "Why? You don't like Nepali guys?"

> "You're right; don't do it. Nepali men aren't good."

"I don't have much time left in country and it's not practical," I say.

> "Well, if you marry a Nepali guy you can get Nepali citizenship, right?"

> "Can't you extend your visa?"

I say something -- anything -- else, to politely express my disinterest.

> "I'll look for matches for you, don't worry!"

There's a secondary set of question-conversation chains that include "Do you cook for yourself at your house?" which sets off a conversation about diet and food in Nepal and the United States. And another: "Does your salary come from the American government or the Nepali government? (Alternatively, "Does your salary come in American dollars or Nepali dollars?") which kicks off another scripted conversation about the reality of my volunteer stipend. The latter requires me to double down when I talk about money, because people go into the conversation expecting me to make a lot of it; and when I tell them how much I make in plain terms they assume my inferior Nepali is interfering with my ability to properly express myself (no, it's not - I am plainly and clearly expressing myself - yes, I only make that much per month).

Any comment of mine follows with cascading probability response branches from a Nepali resident, until, inevitably, another question gets asked from the top of the chart, which triggers another nested cluster of probabilities to expand. Again. and again.

For me, it's not the potentially private nature of these questions that bothers me - it is, quite honestly, the sheer repetition and predictability of them. I sometimes use humor to play with people, but it only gets me so far.

It's part of our job to endure. And another part of it to engage. In the grand scheme of things, this is a small complaint to have, like many other small and insignificant complaints that stack up one atop the other. These interactions also speak to the openness and friendliness of the people here - quick to connect and bond with strangers, generous and playful even in their naivety. Certainly, this type of reception is one of the things that makes Nepal so special. Just happens to make me a bit tired, sometimes, as well.

I suspect in two years' time it will mean very little; that I'll be reminiscing on these moments with nostalgia and amusement.

Last week I was on my way home from a trip to the local market. I hopped into a minivan heading toward my local junction, sharing the passenger seat in front with an older woman. We had some chit-chat. She inevitably asked after my marriage status, and later, about my salary -- that whole conversation we covered in five minutes. That was fine, and we rode the next 20 minutes in relative silence, until I got off at my stop.

I decided to visit a family who operates a shop on the corner of the junction - just to catch up, say hi and rest a few minutes. It had been a while.

As I approached there were some strangers seated at the bench in front of the open stand. They eyeballed me with interest. After being here awhile you begin to recognize the "Who is this foreigner?" look in their face before they inevitably turn to the Nepali companion aside them to talk about you. "Who is this foreigner, huh?" they mused.

"Oh, she lives here! She speaks Nepali! She can understand everything," the shop owners exclaimed. Here we go, I thought.

I kept quiet as long as I could, but someone eventually egged me to confirm that I was from the States when the speaker wasn't believed. "Where are you from?" the lady asked me.

"The United States," I confirmed. Thus kicked off a conversation I was very familiar having: explaining the nature of my meals being cooked by my host mother, my stipend situation, and again about my marriage status (which went on at length...). Even more exasperating is that I am certain that I had had this exact conversation about my stipend and marriage with the shopkeeper family before; yet and here we were, at it again. In the same place. On the same topics.

I was agitated. With all semblance of the relaxing 10 minute respite I was hoping for gone, I politely excused myself, said goodbye and started the hike back up to my village.

Feeling particularly affected that day, I pulled out my phone and sent a frustrated voice message to a friend of mine about how tired I was -- tired of talking about my stipend, about talking about having a mother, father, elder sibling, and two younger siblings, and where they all lived and what they did for a living, tired of talking about my marriage status and then justifying it, and tired of entertaining people who thought they were original and funny and weakly joking about attaching to me, a visa trump card. Tired of all the same.

About ten minutes later I was paused at a resting point on the trail when an elderly man crossed paths with me and stopped for a chat.

"Where are you from?" he asked.

"The United States," I said behind a tired smile.

"The United States!" He exclaimed. "Well, take me to US with you, won't you!"

I wasn't sure what would feel more therapeutic: crying or laughing.

"Sure," I said.